Nembutal oral solution

Nembutal oral solution Lathal dose for Euthanasia

Phenobarbital Oral Solution Description

Barbiturates are nonselective central nervous system (CNS) depressants that are primarily used as sedative-hypnotics. In subhypnotic doses, they are also used as anticonvulsants. Barbiturates and their sodium salts are subject to control under the Federal Controlled Substances Act. Phenobarbital is a barbituric acid derivative and occurs as white, odorless, small crystals or crystalline powder that is very slightly soluble in water; soluble in alcohol, in ether, and solutions of fixed alkali hydroxides and carbonates; and sparingly soluble in chloroform. Phenobarbital is 5-ethyl-5-phenylbarbituric acid and has the empirical formula C 12H 12N 2O 3. Its molecular weight is 232.24. It has the following structural formula: Pentobarbital oral solution (PB) is a euthanasia drug in doses of 2 to 10 grams, causing death within 15–30 minutes. We report a case of recovery from lethal pentobarbital deliberate self-poisoning with confirmatory serum drug concentrations.

Case Report

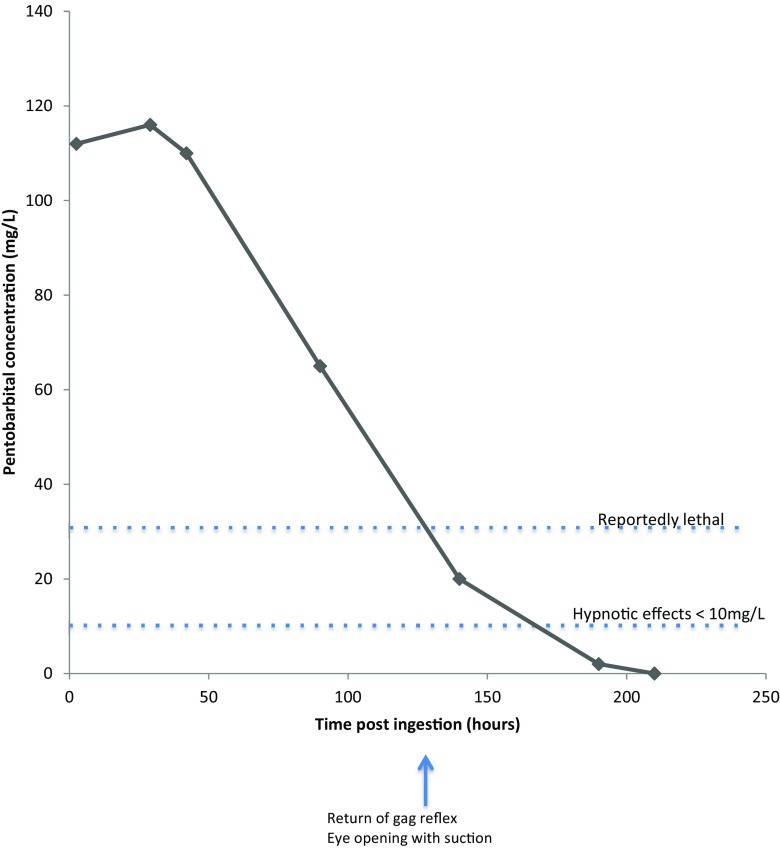

A 45-year-old male purchased 20 grams of PB powder over the Internet. He ingested this powder and then alerted his mother 10 minutes later. She found him unresponsive and commenced cardiopulmonary resuscitation (CPR). Within 20 minutes of ingestion, emergency medical services arrived and initiated advanced life support. On arrival to the emergency department, his heart rate was 116 bpm, BP 117/62 mmHg, and he was on an epinephrine infusion. He was hypotonic and hypothermic, with absent brainstem reflexes. ECG and CT brain were normal. Activated charcoal was administered, and he was admitted to the ICU. He remained comatose with absent brainstem reflexes until day 5. The cerebral angiogram on day 3 was normal. Qualitative urine testing detected pentobarbital, suggesting ongoing drug effects as the cause of the coma. He was extubated on day 10, eventually making a full recovery. At 2.5 hours post-ingestion, PB concentration was 112 mg/L; PB peaked at 116 mg/L at 29 hours; PB was 2 mg/L at 190 hours and undetectable over 200 hours post-ingestion.

Discussion

The average PB concentration in fatalities is reported to be around 30 mg/L. This patient survived higher serum concentrations with early CPR and prolonged cardiorespiratory support in the ICU. Assessment of brainstem death should be deferred until PB has been adequately eliminated.

Pentobarbital (Nembutal) is a short-acting barbiturate sedative-hypnotic that is widely used in veterinary practice for anesthesia and euthanasia. It is also recommended as a drug for euthanasia or assisted suicide due to its rapid onset of coma and perception of a peaceful death. These popular media reports of pentobarbital being a peaceful method of suicide have led to increased interest in obtaining it from jurisdictions where it is less regulated [1]. It is unlikely that any resuscitative measures will be undertaken in these circumstances.

We report a case of survival following deliberate self-poisoning with a potentially lethal dose of pentobarbital obtained via the Internet, in a patient who regretted his actions and sought help almost immediately. Confirmatory serial serum drug concentrations are presented in the context of the patient’s clinical course.

Case History

A 45-year-old male impulsively ingested 20 grams of pentobarbital (Nembutal) that he had purchased via the Internet from a source overseas 2 years previously. He had a history of bipolar affective disorder, trigeminal neuralgia, and chronic pain. His regular medications included venlafaxine, gabapentin, and asenapine. He alerted his mother 10 minutes after taking the overdose. She immediately contacted emergency medical services (EMS). When she returned to him, he was on the floor and unconscious, and she immediately commenced cardiopulmonary resuscitation (CPR). EMS arrived 10 minutes after the call (approximately 20 minutes post-ingestion) and found him to be in a pulseless electrical activity cardiac arrest. CPR continued, and advanced life support (ALS) measures were commenced. He received two intravenous doses of 1 mg epinephrine during initial resuscitation, with return of spontaneous circulation (ROSC) occurring after 10 min. The patient was intubated and ventilated. He had a further brief cardiac arrest 30 minutes later, with ROSC being achieved after another 2 minutes of CPR and a further 1 mg epinephrine. He was commenced on an epinephrine infusion at 100 μg/min, given a 500-mL normal saline bolus, and transported to the emergency department (ED).

The patient arrived in the ED 95 minutes after the initial call to EMS. On presentation, he was unconscious (GCS 3/15) with no additional sedation, had fixed dilated pupils, and was apnoeic on the ventilator with absent brainstem reflexes. He was hypothermic (33.8 °C). Heart rate was 116 bpm, and BP was 117/62 mmHg on an epinephrine infusion at 100μg/min. Venous blood gas showed pH 7.02, pCO2 60 mmHg, HCO3 15 mmol/L, and 11.9 mmol/L lactate. Serum ethanol, paracetamol, and salicylate were undetectable. ECG was unremarkable,e and CT brain revealed no acute abnormality. A single dose of 50 g activated charcoal was administered via NGT and he was admitted to the ICU.

The decision was made to treat supportively and not institute any extracorporeal elimination techniques. On day 1 in ICU, he developed polyuria, with urine output peaking at 300 mL/h, and hypernatraemia (serum Na 149 mmol/L), so he was treated with one dose of desmopressin.

He required vasopressor support with norepinephrine infusion (peak dose of 30 μg/min) for the first 5 days of his admission. He remained comatose without sedation, with absent brainstem reflexes, prompting discussions around the diagnosis of brain death. A four-vessel cerebral angiogram was performed on day 3. This showed normal cerebral perfusion. Urine sent for qualitative analysis by gas chromatography-mass spectrometry (GC-MS) detected pentobarbital, confirming ongoing drug effects as the likely cause for persistent coma. On day 5, there was a return of the gag reflex on suctioning and eye opening to painful stimuli. Propofol infusion was commenced to enable endotracheal tube tolerance from day 7. However, extubation was delayed due to the development of aspiration pneumonitis. He was finally extubated on day 10 post-overdose and was discharged to the medical ward the next day. He required an additional 10 days in the hospital for ongoing treatment of his aspiration pneumonitis and physiotherapy for reconditioning. He made a complete neurological recovery and confirmed the ingestion of 20 grams of pentobarbital powder mixed with water. He was discharged to an inpatient mental health facility on day 22 post-overdose. He remained an inpatient there for a further 3 weeks before being discharged home, with ongoing outpatient psychiatric follow-up.

Serial serum pentobarbital concentrations were retrospectively assayed by high-performance liquid chromatography/mass spectrometry (HPLC/MS) and are summarised in Fig. 1. Peak concentration was 116 mg/mL at approximately 29 hours post-ingestion (therapeutic 1.8–4.7 mg/L).

Fig. 1.

Written consent for publication of this case was obtained and provided to the journal.

Phenobarbital Oral Solution – Clinical Pharmacology

Barbiturates are capable of producing all levels of CNS mood alteration, from excitation to mild sedation, hypnosis, and deep coma. Overdosage can produce death. In high enough therapeutic doses, barbiturates induce anesthesia.

Barbiturates depress the sensory cortex, decrease motor activity, alter cerebellar function, and produce drowsiness, sedation, and hypnosis.

Barbiturate-induced sleep differs from physiologic sleep. Sleep laboratory studies have demonstrated that barbiturates reduce the amount of time spent in the rapid eye movement (REM) phase of sleep or the dreaming stage. Also, in Stages III and IV, sleep is decreased. Following abrupt cessation of barbiturates used regularly, patients may experience markedly increased dreaming, nightmares, and/or insomnia. Therefore, withdrawal of a single therapeutic dose over 5 or 6 days has been recommended to lessen the REM rebound and disturbed sleep that contribute to the drug withdrawal syndrome (for example, the dose should be decreased from 3 to 2 doses/day for 1 week).

In studies, secobarbital sodium and pentobarbital sodium have been found to lose most of their effectiveness for both inducing and maintaining sleep by the end of 2 weeks of continued drug administration, even with the use of multiple doses. As with secobarbital sodium and pentobarbital sodium, other barbiturates (including amobarbital) might be expected to lose their effectiveness for inducing and maintaining sleep after about 2 weeks. The short-, intermediate-, and, to a lesser degree, long-acting barbiturates have been widely prescribed for treating insomnia. Although the clinical literature abounds with claims that the short-acting barbiturates are superior for producing sleep whereas the intermediate-acting compounds are more effective in maintaining sleep, controlled studies have failed to demonstrate these differential effects. Therefore, as sleep medications, barbiturates are of limited value beyond short-term use.

Barbiturates have little analgesic action at subanesthetic doses. Rather, in subanesthetic doses, these drugs may increase the reaction to painful stimuli. All barbiturates exhibit anticonvulsant activity in anesthetic doses. However, of the drugs in this class, only phenobarbital, mephobarbital, and metharbital are effective as oral anticonvulsants in subhypnotic doses.

Barbiturates are respiratory depressants, and the degree of respiratory depression is dependent upon the dose. With hypnotic doses, respiratory depression produced by barbiturates is similar to that which occurs during physiologic sleep and is accompanied by a slight decrease in blood pressure and heart rate.

Studies in laboratory animals have shown that barbiturates cause reductions in the tone and contractility of the uterus, ureters, and urinary bladder. However, concentrations of the drugs required to produce this effect in humans are not reached with sedative/hypnotic doses.

Barbiturates do not impair the normal hepatic function but have been shown to induce liver microsomal enzymes, thus increasing and/or altering the metabolism of barbiturates and other drugs (see Drug Interactions under PRECAUTIONS).

PHARMACOKINETICS

Barbiturates are absorbed in varying degrees following oral or parenteral administration. The salts are more rapidly absorbed than are the acids. The rate of absorption is increased if the sodium salt is ingested as a dilute solution or taken on an empty stomach.

Duration of action, which is related to the rate at which the barbiturates are redistributed throughout the body, varies among persons and in the same person from time to time.

Phenobarbital is classified as a long-acting barbiturate when taken orally. Its onset of action is 1 hour or longer, and its duration of action ranges from 10 to 12 hours.

Barbiturates are weak acids that are absorbed and rapidly distributed to all tissues and fluids, with high concentrations in the brain, liver, and kidneys. Lipid solubility of the barbiturates is the dominant factor in their distribution within the body. The more lipid soluble the barbiturate, the more rapidly it penetrates all tissues of the body. Barbiturates are bound to plasma and tissue proteins to a varying degree with the degree of binding increasing directly as a function of lipid solubility.

Phenobarbital has the lowest lipid solubility, lowest plasma binding, lowest brain protein binding, the longest delay in onset of activity, and the longest duration of action. The plasma half-life for phenobarbital in adults ranges between 53 and 118 hours with a mean of 79 hours. The plasma half-life for phenobarbital in children and newborns (less than 48 hours old) ranges between 60 to 180 hours with a mean of 110 hours.

Barbiturates are metabolized primarily by the hepatic microsomal enzyme system, and the metabolic products are excreted in the urine, and, less commonly, in the feces. Approximately 25% to 50% of a dose of phenobarbital is eliminated unchanged in the urine. The excretion of unmetabolized barbiturate is one feature that distinguishes the long-acting category from those belonging to other categories, which are almost entirely metabolized. The inactive metabolites of the barbiturates are excreted as conjugates of glucuronic acid.

Indications and Usage for Nembutal Oral Solution

A. Sedative

B. Anticonvulsant – For the treatment of generalized and partial seizures.

Contraindications

Phenobarbital is contraindicated in patients who are hypersensitive to barbiturates, in patients with a history of manifest or latent porphyria, and in patients with marked impairment of liver function or respiratory disease in which dyspnea or obstruction is evident.

Warnings

1. Habit Forming

Phenobarbital may be habit-forming. Tolerance and psychological and physical dependence may occur with continued use (see DRUG ABUSE AND DEPENDENCE and Pharmacokinetics under CLINICAL PHARMACOLOGY). Patients who have psychological dependence on barbiturates may increase the dosage or decrease the dosage interval without consulting a physician and may subsequently develop a physical dependence on barbiturates. In order to minimize the possibility of overdosage or the development of dependence, the prescribing and dispensing of sedative-hypnotic barbiturates should be limited to the amount required for the interval until the next appointment. Abrupt cessation after prolonged use in a person who is dependent on the drug may result in withdrawal symptoms, including delirium, convulsions, and possibly death. Barbiturates should be withdrawn gradually from any patient known to be taking excessive doses over long periods of time (see DRUG ABUSE AND DEPENDENCE).

2. Acute or Chronic Pain

Caution should be exercised when barbiturates are administered to patients with acute or chronic pain because paradoxical excitement could be induced or important symptoms could be masked. However, the use of barbiturates as sedatives in the postoperative surgical period and as adjuncts to cancer chemotherapy is well established.

3. Usage in Pregnancy

Barbiturates can cause fetal damage when administered to a pregnant woman. Retrospective, case-controlled studies have suggested a connection between the maternal consumption of barbiturates and a higher-than-expected incidence of fetal abnormalities. Barbiturates readily cross the placental barrier and are distributed throughout fetal tissues; the highest concentrations are found in the placenta, fetal liver, and brain. Fetal blood levels approach maternal blood levels following parenteral administration.

Withdrawal symptoms occur in infants born to women who receive barbiturates throughout the last trimester of pregnancy (see DRUG ABUSE AND DEPENDENCE).

If Phenobarbital is used during pregnancy or if the patient becomes pregnant while taking this drug, the patient should be apprised of the potential hazard to the fetus.

4. Usage in Children

Phenobarbital has been reported to be associated with cognitive deficits in children taking it for complicated febrile seizures.

5. Synergistic Effects

Precaution

Barbiturates may be habit-forming. Tolerance and psychological and physical dependence may occur with continued use (see DRUG ABUSE AND DEPENDENCE).

Barbiturates should be administered with caution, if at all, to patients who are mentally depressed, have suicidal tendencies, or have a history of drug abuse.

Elderly or debilitated patients may react to barbiturates with marked excitement, depression, or confusion. In some persons, especially children, barbiturates repeatedly produce excitement rather than depression.

In patients with hepatic damage, barbiturates should be administered with caution and initially in reduced doses. Barbiturates should not be administered to patients showing the premonitory signs of hepatic coma.

The systemic effects of exogenous and endogenous corticosteroids may be diminished by Phenobarbital. Thus, this product should be administered with caution to patients with borderline hypoadrenal function, regardless of whether it is of pituitary or of primary adrenal origin.

Information for Patients

The following information and instructions should be given to patients receiving barbiturates.

1. The use of barbiturates carries with it an associated risk of psychological and/or physical dependence. The patient should be warned against increasing the dose of the drug without consulting a physician.

2. Barbiturates may impair the mental and/or physical abilities required for the performance of potentially hazardous tasks, such as driving a car or operating machinery. The patients should be cautioned accordingly.

3. Alcohol should not be consumed while taking barbiturates. The concurrent use of barbiturates with other CNS depressants (eg., alcohol, narcotics, tranquilizers, and antihistamines) may result in additional CNS-depressant effects.

References

- 1.Cantrell FL, Nordt S, McIntyre I, Schneir A. Death on the doorstep of a border community—intentional self-poisoning with veterinary pentobarbital. Clin Toxicol. 2010;48:849–850. doi: 10.3109/15563650.2010.512562. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bosshard G, Ulrich E, Bar W. 748 cases of suicide assisted by a Swiss right-to-die organization. Swiss Med Wkly. 2003;133:310–317. doi: 10.4414/smw.2003.10212. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Mactier R, Laliberte M, Mardini J, Ghannoum M, Lavergne V, et al. Extracorporeal treatment for barbiturate poisoning: recommendations from the EXTRIP Workgroup. Am J Kidney Dis. 2014;64:347–358. doi: 10.1053/j.ajkd.2014.04.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Roberts DM, Buckley NA. Enhanced elimination in acute barbiturate poisoning—a systematic review. Clin Toxicol. 2011;49:2–12. doi: 10.3109/15563650.2010.550582. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Heinemeyer G, Roots I, Dernhardt R. Monitoring of pentobarbital plasma levels in critical care patients suffering from increased intracranial pressure. Ther Drug Monit. 1986;8:145–150. doi: 10.1097/00007691-198606000-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.McCarron MM, Schulze BW, Walberg CB, Thompson GA, Ansari A. Short acting barbiturate overdosage. Correlation of intoxication score with serum barbiturate concentration. JAMA. 1982;248:55–61. doi: 10.1001/jama.1982.03330010029026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Sullivan R, Hodgman MJ, Kao L, Tormoehlen LM. Baclofen overdose mimicking brain death. Clin Toxicol. 2012;50:141–144. doi: 10.3109/15563650.2011.654209. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Neavyn MJ, Stolbach A, Greer DM, Nelson LS, Smith SW, et al. ACMT position statement: determining brain death in adults after drug overdose. J Med Toxicol. 2017;13:271–273. doi: 10.1007/s13181-017-0606-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Be the first to review “Nembutal oral solution” Cancel reply

Related products

Nembutal

Nembutal

Reviews

There are no reviews yet.